BCFS: Object File Generation and the ELF Format — Part I

Dec 14, 2025 · Hong-Sheng ZhengI built a strong wall that cannot be shaken with bitumen and baked bricks… I laid its foundation on the breast of the netherworld, and I built its top as high as a mountain.

Nebuchadnezzar II (604–562 B.C.)

Hardware is the ultimate reality.

While we may dream up sophisticated designs and optimizations for programming languages or compilers,

even the most ‘blue-sky’ abstractions must eventually touch the ground.

They must materialize as instructions that hardware can actually execute.

If a language’s semantics detach from the physical realities of the underlying architecture…

then it likely won’t end well. For example,

can you imagine a language for a systolic array AI engine attempting to handle matrix multiplication

via pixel-wise for loops rather than tensor operations?

In this post, we will introduce the gap between the compiler and linker as needed. We will not cover too many details, and some concepts may seem complex, but don’t worry if you don’t fully understand everything in this post. The main purpose of this article is to help readers of Part II clearly distinguish what belongs to the compiler’s responsibility and what doesn’t, which will help reduce ambiguity in what follows. Yes, we will have Part II 🤣. In the next post, we will return to real object file generation and start building the first object file with Executable and Linkable Format (ELF).

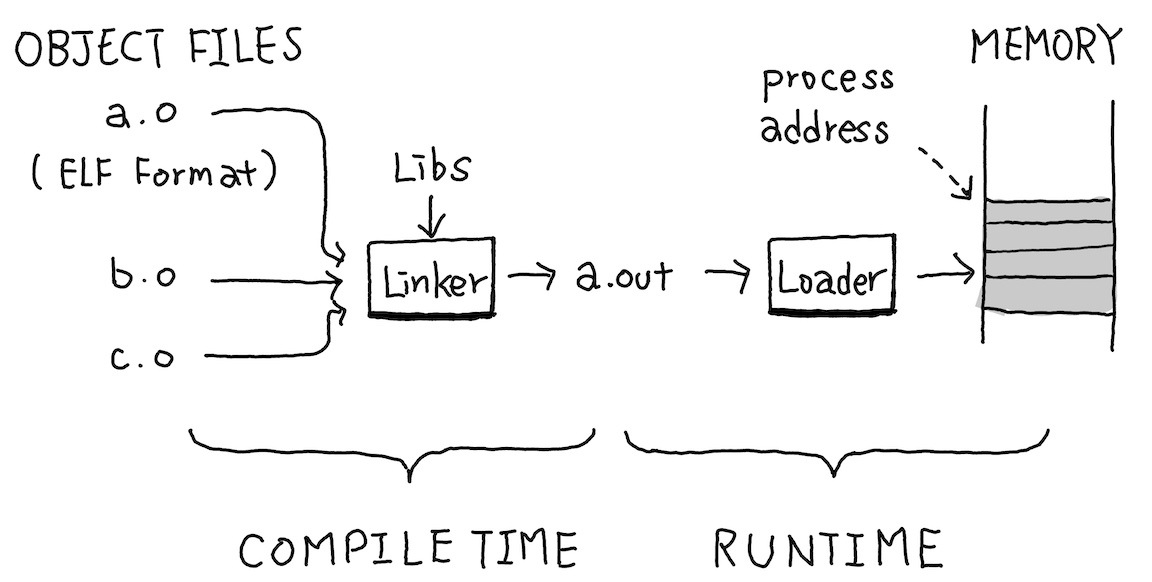

Object Files and the Road to Execution

Before we jump into object file generation, let’s first understand how an object file becomes an executable, and what exactly bridges the gap between them. In traditional compilers, which consist of a frontend and a backend, instruction selection typically marks the boundary between the two. Object file generation is essentially the final stage of the compiler. It produces the object file, and it’s nearly ready to run, just one step away from becoming an executable, the Linking. Once linking is complete, the resulting binary contains everything needed for execution. The operating system then loads it into memory and starts running it.

At first glance, you might picture this process simply: the compiler generates machine instructions, the linker glues them together with code from other object files or libraries into one long stream of machine code, and the OS loader drops that sequence somewhere in memory and starts executing from the top.

Hmmm… while that mental model isn’t too far off, there are quite a few issues when you get into the details. Let’s walk through them step by step to see what the problems are. Actually, we only need to answer two questions to understand roughly how the linker works.

➊ First, let’s look into an example. In the code below, if you want to execute printf,

where does printf come from? If you trace through stdio.h, you’ll find it’s just a function declaration sitting there,

the actual implementation isn’t anywhere in your code. Well, that’s true, the implementation is probably in your glibc’s libc.so.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello World\n");

return 0;

}And in assembly, when you want to execute a function, a function call is essentially just a jump instruction

(there’s more to function calls, but let’s not get into that now).

But we don’t know where printf is, how do we know where to jump? How do we know what address to use?

You might immediately think: if I have two object files, after I glue them together, as long as I can control where the loader loads my program into memory (start_address),

then I can find the location of the function I need from the other object file, and I can know the absolute position of the function I glued together (start_address + offset),

so I can just jump to that address! Indeed! You can glue them together. But there is a cost,

the binary size will increase signficantly. You can try compiling the code above, once with gcc hello.c -o hello.out (dynamic linking by default),

and once with gcc hello.c -static -o hello_static.out (which is called static linking).

The size of the result binary from the first one will be roughly 16 KiB,

while the static one will require 712 KiB. So most of the time, we won’t use static linking, since it bloats the binary significantly, every program duplicates the same library code.

And obviously, if we don’t use static linking, the address that this instruction jumps to must be determined at some point.

However, in practice, most programs are compiled as position-independent executables (PIE) in major Linux distributions, and OS implement ASLR by default, meaning the starting address is resolved at runtime rather than being statically fixed.

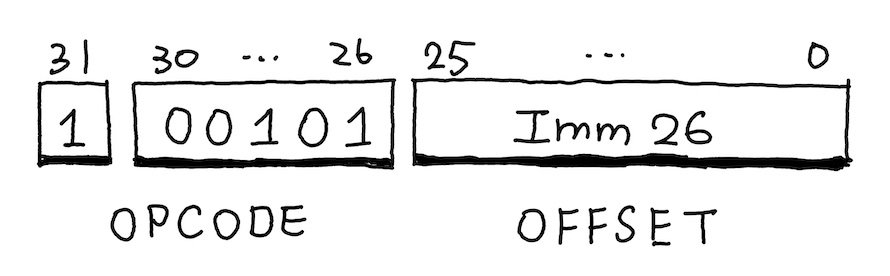

Building on the previous question, ARM commonly uses an instruction bl for function calls,

which is an instruction that can jump to the beginning of a function.

The bl instruction encodes a 26-bit signed offset. Since ARM instructions are 4-byte aligned,

this gives a maximum range of

In practice, functions inside a single executable are usually much closer than 128 MiB,

so this range limitation rarely becomes a problem.

But what if the target does lie outside the bl instruction simply cannot reach it directly.

➋ So who’s responsible for ensuring that no bl target falls outside the blr (branch with link to register) instruction,

which jumps to a full 64-bit address stored in a register. Wouldn’t that give unlimited range?

That’s a good point! blr does indeed eliminate the range limit.

However, using it requires first loading the 64-bit target address into a register,

which typically takes two instructions: adrp and add.

adrp x17, func@PAGE ; Load the page base (high bits)

add x17, x17, func@PAGEOFF ; Add the page offset (low bits)

blr x17 ; Indirect call with linkCompared to a single bl, this sequence increases code size (3 instructions instead of 1),

and hurts performance: it adds extra instruction latency and, more importantly,

turns the call into an indirect branch. Indirect branches are harder for the CPU to predict,

leading to more branch mispredictions and higher penalties when they occur.

For these reasons, modern toolchains strongly prefer the single instruction bl whenever possible.

1. Where Does printf Come From?

The answer to this question is called Relocation,

It’s not just about the printf function, any reference that requires a memory address faces the same challenge.

This includes global variables, functions defined in other source files, symbols from static or dynamic libraries…

and even the address of a simple string literal like "Hello World". At compile time, the compiler has no way of knowing where it will end up in the final binary,

so the resolution of these addresses must be deferred.

This process relies heavily on the cooperation between the linker (the static linker) and the loader (the dynamic loader, ld.so on Linux).

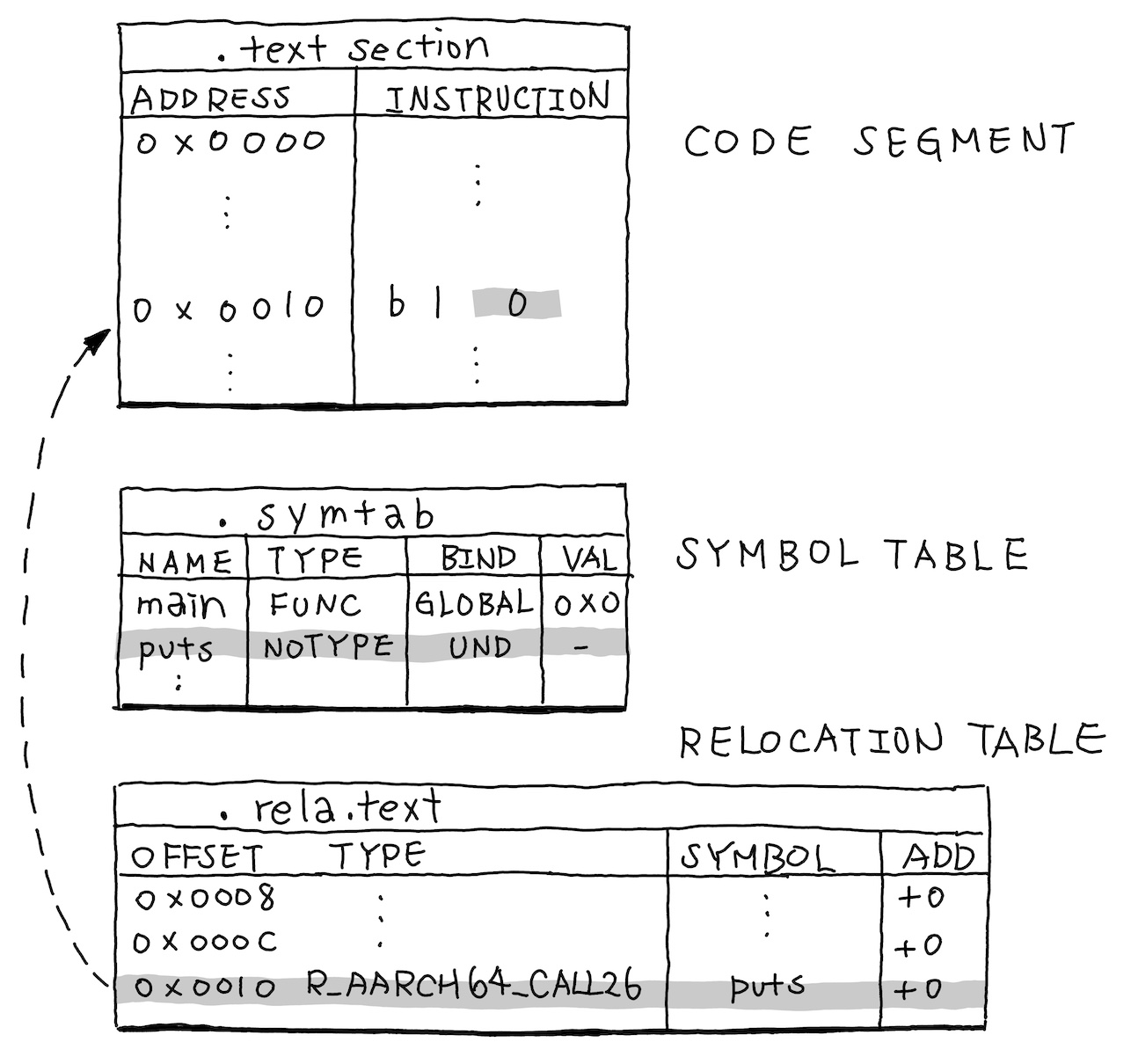

From the compiler’s perspective, it knows it needs to emit a bl instruction, but it doesn’t know the target address.

So it temporarily fills in an offset of 0 as a placeholder.

At the same time, it records two critical pieces of information in the object file to hand off to the next stage, the linker:

- Symbol Table (.symtab): This table lists all symbols in the current file along with their status. It marks the

putsasUND(Undefined). - Relocation Table (.rela.text): This table records exactly which instructions need to be patched later. The location of the instruction (offset within the

.textsection). the relocation type (e.g.,R_AARCH64_CALL26, which tells the linker: This is ablinstruction, needed to patch the 26-bit offset”), and the name of the symbol to be resolved (e.g.,puts)

And that’s the full extent of the compiler’s responsibility when it comes to address resolution. Now we are good to continue to see what linker does for us.

When GCC detects that

printfis only printing a plain string, it automatically optimizes it toputs. You may be wondering: how is this possible? It’s a function, so how can the compiler know the semantics of this function and replace it with another function?#include <stdio.h> int printf(const char* format, ...) { return 42; } int main() { printf("Why it print this line?\n"); fprintf(stderr, "Done\n"); return 0; }Actually, it doesn’t know. It gets replaced with

putsjust based on the function signature in IR. You can compile it withgcc <filename> -o a.outand try running it.

The task is now handed over to the linker. The linker will solve what it can, delegate the rest.

Once The linker receives all the object files and any specified libraries, it attempts to resolve these relocations.

If puts just comes from a static library (e.g., libc.a), the linker can locate it, calculate the correct offset, and patch the bl instruction directly.

However, if puts resides in libc.so. The linker cannot determine the final runtime address because the shared library is loaded only at runtime,

and its base address may vary due to ASLR.

At this point, the linker cannot fill in the real address, but it performs a crucial transformation: it rewrites the program into a form that can be resolved at runtime. It generates the following key structures in the final executable:

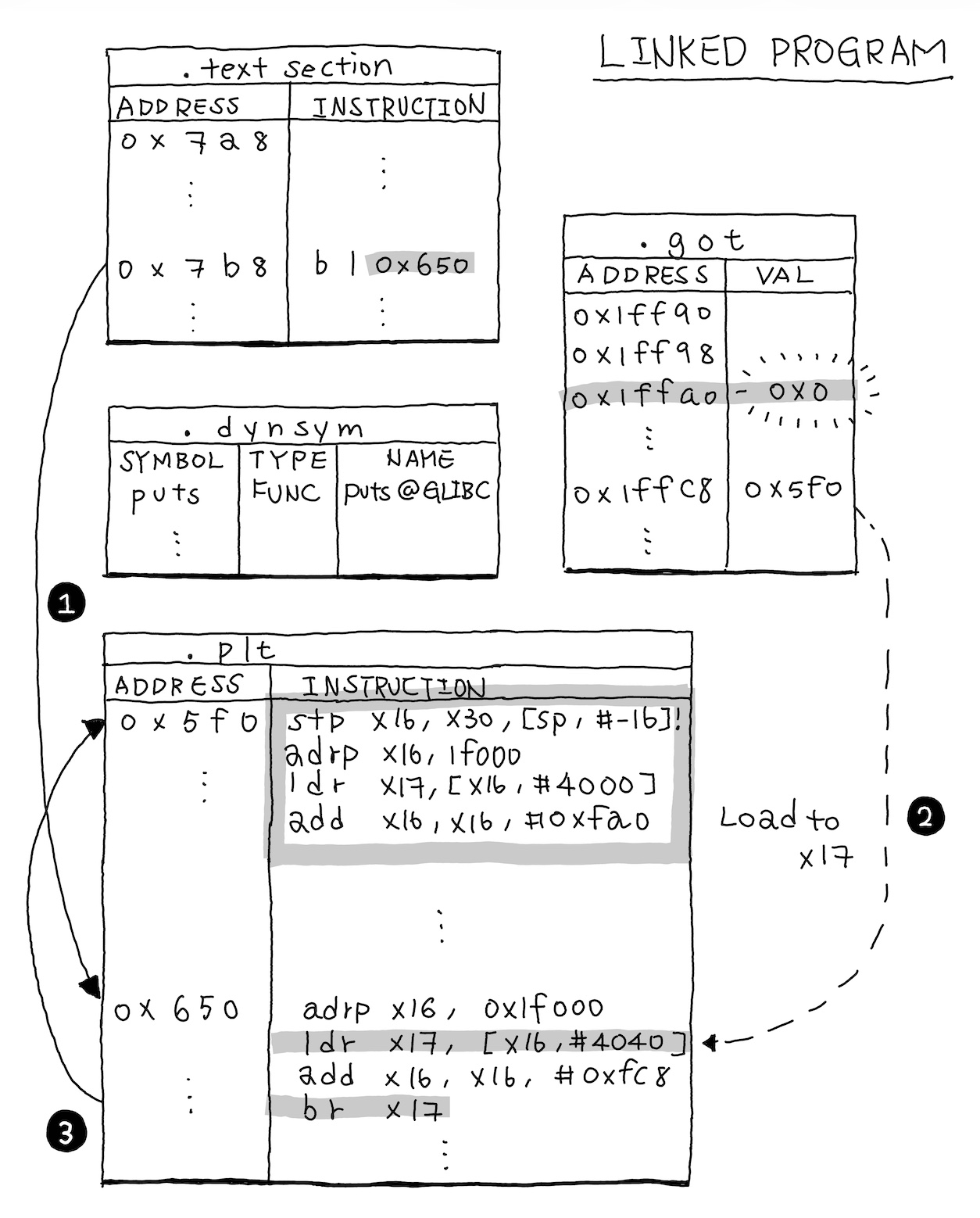

Dynamic Symbol Table (.dynsym): A stripped-down symbol table containing only the symbols that require runtime resolution (e.g.,

puts). Each entry records the symbol name (pointing into.dynstr, not shown here), type, and other metadata.Global Offset Table (.got): GOT, A table of addresses, with one entry per external function.

Procedure Linkage Table (.plt): PLT, A series of small code stubs, one for each external function. The original

bl 0is rewritten to jump to the corresponding PLT stub.Relocation Table (.rela.plt): It’s not shown here, but this is the critical piece that tells the dynamic linker how to resolve symbols. Each entry specifies:

- Offset: Which GOT entry to patch (e.g.,

0x1ffc8forputs) - Type: What kind of relocation (

R_AARCH64_JUMP_SLOTfor lazy binding) - Symbol: Which symbol to resolve (index into

\.dynsympointing to “puts”) Without\.rela.plt, the dynamic linker wouldn’t know that address of GOT entry corresponds to the symbol “puts” in “libc.so.6”.

- Offset: Which GOT entry to patch (e.g.,

Well, let’s step by step to see what happens then:

If you trace the generated executable using objdump and readelf,

you’ll notice that when executing puts, the process jumps to a GOT entry (0x1ffa0 here)

with a value of 0. Actually, when the program starts, the dynamic linker first initializes 0x1ffa0

in GOT with the address of _dl_runtime_resolve, which is used to resolve the address at runtime.

So the process of executing puts follows this flow:

- Fir jump to

puts@plt(0x650) - Load address from

0x1ffc8and gets0x5f0(PLT header) - Jump to PLT header, which calls

_dl_runtime_resolvevia0x1ffa0 _dl_runtime_resolveuses.rela.pltto find that0x1ffc8needs"puts@GLIBC_2.17"- Resolves the real address and patches

0x1ffc8 - Subsequent calls jump directly to the real

puts

Now we have a clear picture of where printf comes from 😃 and what role the compiler plays.

Looking at the final executable, you’ll notice additional components that aren’t typically

considered during compiler design, things like .rela.plt, .dynsym, .got, and .plt.

These are structures you’ll run into when debugging, even though they’re generated by the linker

and dynamic linker rather than the compiler itself.

Here is a list of commands you can try on your computer to trace the flow and observe the same structures we discussed previously:

After you compile hello.c to a.out:

gcc hello.c -o a.outWe can use objdump to get the disassembly code:

objdump -d a.out...

Disassembly of section .plt:

00000000000005f0 <.plt>:

5f0: a9bf7bf0 stp x16, x30, [sp, #-16]!

5f4: f00000f0 adrp x16, 1f000 <__abi_tag+0x1e714>

5f8: f947d211 ldr x17, [x16, #4000]

5fc: 913e8210 add x16, x16, #0xfa0

600: d61f0220 br x17

604: d503201f nop

608: d503201f nop

60c: d503201f nop

...

0000000000000650 <puts@plt>:

650: f00000f0 adrp x16, 1f000 <__abi_tag+0x1e714>

654: f947e611 ldr x17, [x16, #4040]

658: 913f2210 add x16, x16, #0xfc8

65c: d61f0220 br x17

Disassembly of section .text:

...

00000000000007a8 <main>:

7a8: a9bf7bfd stp x29, x30, [sp, #-16]!

7ac: 910003fd mov x29, sp

7b0: 90000000 adrp x0, 0 <_init-0x5d0>

7b4: 911fa000 add x0, x0, #0x7e8

7b8: 97ffffa6 bl 650 <puts@plt>

7bc: 52800000 mov w0, #0x0 // #0

7c0: a8c17bfd ldp x29, x30, [sp], #16

7c4: d65f03c0 retWe can also use readelf to get section information, use -s -j to show the sepecfic section

and -r for relocation sections.

objdump -s -j .got a.outContents of section .got:

1ff90 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 ................

1ffa0 00000000 00000000 f0050000 00000000 ................

1ffb0 f0050000 00000000 f0050000 00000000 ................

1ffc0 f0050000 00000000 f0050000 00000000 ................

1ffd0 a0fd0100 00000000 00000000 00000000 ................

1ffe0 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 ................

1fff0 a8070000 00000000 00000000 00000000 ................readelf -r a.outRelocation section '.rela.dyn' at offset 0x498 contains 8 entries:

...

Relocation section '.rela.plt' at offset 0x558 contains 5 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

00000001ffa8 000300000402 R_AARCH64_JUMP_SL 0000000000000000 __libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.34 + 0

00000001ffb0 000500000402 R_AARCH64_JUMP_SL 0000000000000000 __cxa_finalize@GLIBC_2.17 + 0

00000001ffb8 000600000402 R_AARCH64_JUMP_SL 0000000000000000 __gmon_start__ + 0

00000001ffc0 000700000402 R_AARCH64_JUMP_SL 0000000000000000 abort@GLIBC_2.17 + 0

00000001ffc8 000800000402 R_AARCH64_JUMP_SL 0000000000000000 puts@GLIBC_2.17 + 0You should also note that ARM uses little-endian byte order, so when reading hexadecimal values,

you need to read them from right to left (least significant byte first). For example, the value f0050000 00000000

at address 0x1ffa8 represents 0x00000000000005f0 which is the PLT header address.

2. Who’s Responsible for Ensuring That No bl Target Falls Outside the \pm 128 MiB Range

Actually, the compiler does not take responsibility for preventing this situation,

it simply generates a bl instruction assuming the target will be within range,

and leaves the final code layout to the linker. The linker is responsible for

adjusting sections, offsets, and other layout details. When it detects during

layout that a branch target is too far away, it inserts a small intermediate

code stub known as a veneer.

This veneer is placed near the original call site to ensure the initial bl

to the veneer stays within range, and it uses a sequence of instructions

, typically adrp, add and br, to load the full 64-bit address and

perform an unconditional jump.

...

; Original call site (too far from target)

bl far_function_veneer ; Jump to veneer (within range)

...

; Veneer stub (inserted by linker near the call site)

far_function_veneer:

adrp x17, far_function@PAGE ; Load page base (high bits)

add x17, x17, far_function@PAGEOFF ; Add page offset (low bits)

br x17 ; Jump to real targetThanks to veneers, This issue is almost never a problem, even in very large binaries. In practice, functions within a single executable are usually much closer than 128 MiB, so veneers rarely affect internal calls. The linker’s automatic insertion of veneers ensures that even when a direct call exceeds the range, the program still functions correctly, at the cost of slightly larger code size and a minor performance penalty for the indirect jump through the veneer.

Summary and What’s Next

This article is by no means intended to create panic or overwhelm you with complexity. We will revisit these concepts in detail when they become necessary in later parts of the series. The primary purpose of this article is to reduce ambiguity when we start implementing the object file generator in the next part.

By clearly distinguishing what belongs to the compiler’s responsibility and what doesn’t, we can focus solely on the compiler’s tasks in Part II without getting confused about which components we need to implement and which ones are handled by the linker or dynamic loader. This clarity will make the implementation process much smoother.

In the next post, we’ll start building the ELF file generator, focusing exclusively on what the compiler needs to produce.

Further Reading

- linkers-and-loaders, Levine, John R.

- ASLR: On the effectiveness of address-space randomization

- GCC reference code : The reference code for printf to puts optimization based on function signature in IR