BCFS: Object File Generation and the ELF Format — Part II

Jan 6, 2026 · Hong-Sheng ZhengThe difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter. ‘tis the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning

Mark Twain, letter to George Bainton, October 15, 1888

A key piece that turns your program into an executable on Unix-like systems is the Executable and Linkable Format (ELF). Think of ELF as a standardized container for your code and data, a universal “language” that all tools can understand. Just like any PDF reader can open a PDF no matter what software created it. Compilers produce them, linkers merge multiple ones, debuggers extract symbol informations, and the OS loader maps them into memory.

Many folks might worry that crafting ELF files is a nightmare, fields everywhere,

tiny mistakes can crash your program. And yeah, it’s not trivial; you have to follow strict rules.

But at the end of the day, it’s just a file format. After working through this post,

you’ll have a foundation to build upon. You’ll be able to understand how to debug your program,

interpret information from tools like readelf and objdump, and most importantly,

we’ll have an interface to generate object files for our compiler!

In this post, we will build an ELF object file generator from scratch. Rather than drowning you in definitions upfront,

we’ll learn each concept as we need it. By the end, you’ll have a working “Hello World” program

generated entirely by our own code. The complete implementation is available in the

compiler-from-scratch repository under the ch1.1 directory.

Note that code snippets in this post are simplified for clarity, please refer to the repository for the complete implementation.

Our Goal: A Working “Hello World”

Before diving into implementation details, let’s be clear about what we’re building.

Our goal is to generate an object file hello.o that, when linked with gcc, produces a working executable:

$ g++ main_hello.cpp obj_writer.cpp --std=c++20 -o gen

$ ./gen # Run our generator to get `hello.o`

$ gcc -o hello hello.o # Link with system libraries

$ ./hello # Run the program

hello worldThe generated object file hello.o will contain a main function that calls printf to print “hello world”.

This might sound simple, but it requires us to correctly generate:

- Machine code for ARM64 instructions

- A string constant

hello world\n\0in read-only data - Symbol information so the linker knows about

mainandprintf - Relocation entries so the linker can patch addresses

Let’s see what the final disassembly of hello.o will look like:

$ objdump -d hello.o

hello.o: file format elf64-littleaarch64

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000000 <main>:

0: a9bf7bfd stp x29, x30, [sp, #-0x10]!

4: 910003fd mov x29, sp

8: 90000000 adrp x0, 0x0 <main>

c: 91000000 add x0, x0, #0x0

10: 94000000 bl 0x10 <main+0x10>

14: d2800000 mov x0, #0x0 // =0

18: a8c17bfd ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x10

1c: d65f03c0 retYou might notice something odd in the disassembly: the bl instruction shows bl 0x10 <main+0x10>,

which appears to branch to itself. This happens because bl is a PC-relative instruction, and objdump

calculates the target address as the current PC (0x10) plus the offset field (which is 0).

Since the offset hasn’t been filled in by the linker yet, objdump interprets it as “branch to current location.”

Similarly, the adrp and add instructions show adrp x0, 0x0 and add x0, x0, #0x0, their immediate fields

are also zero because they haven’t been patched by the linker yet. These zeros in the adrp, add, and bl instructions

are placeholders that the linker will fill in based on relocation entries.

This is exactly what relocations are for, and we’ll see how they work as we build our generator.

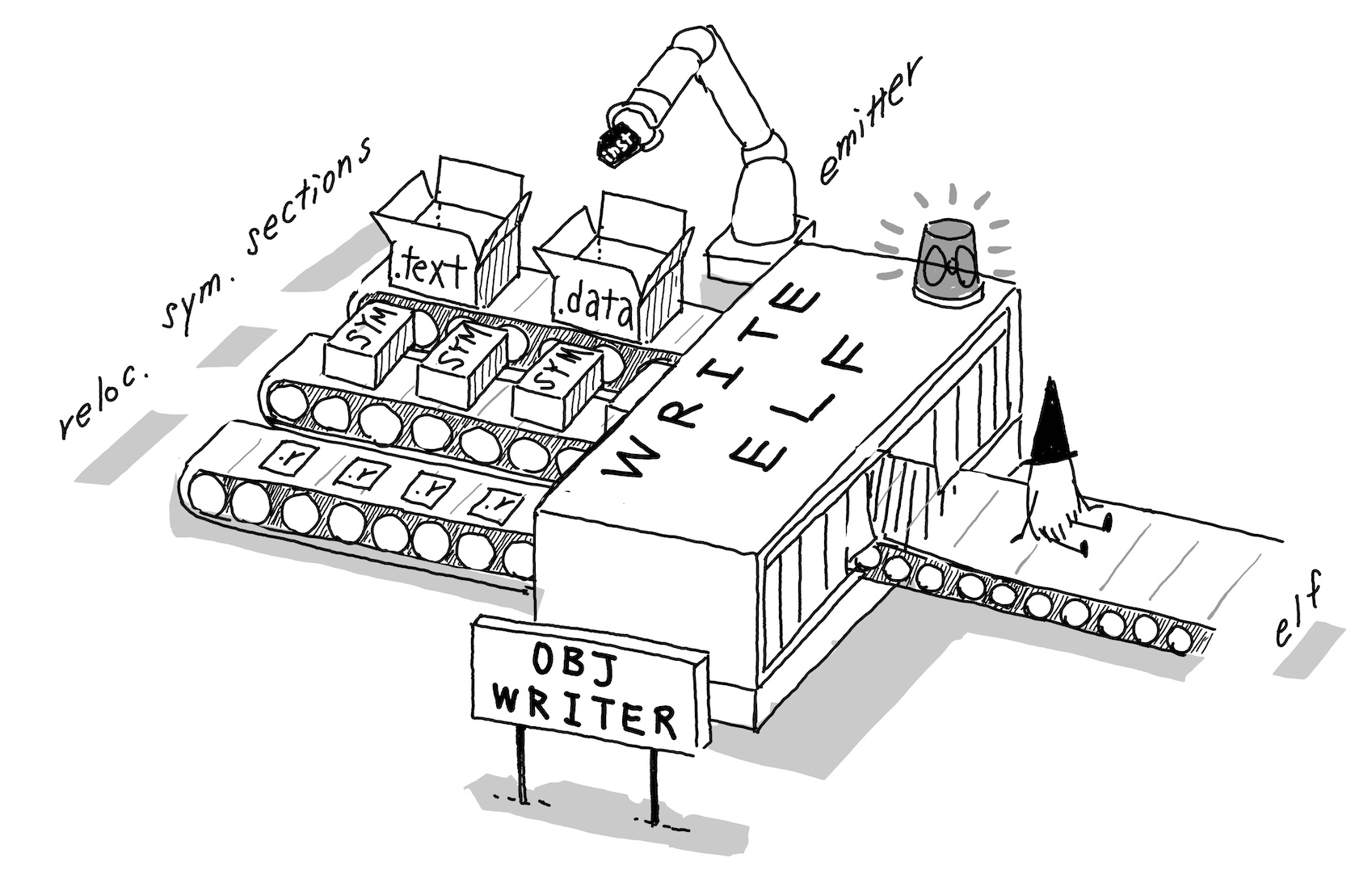

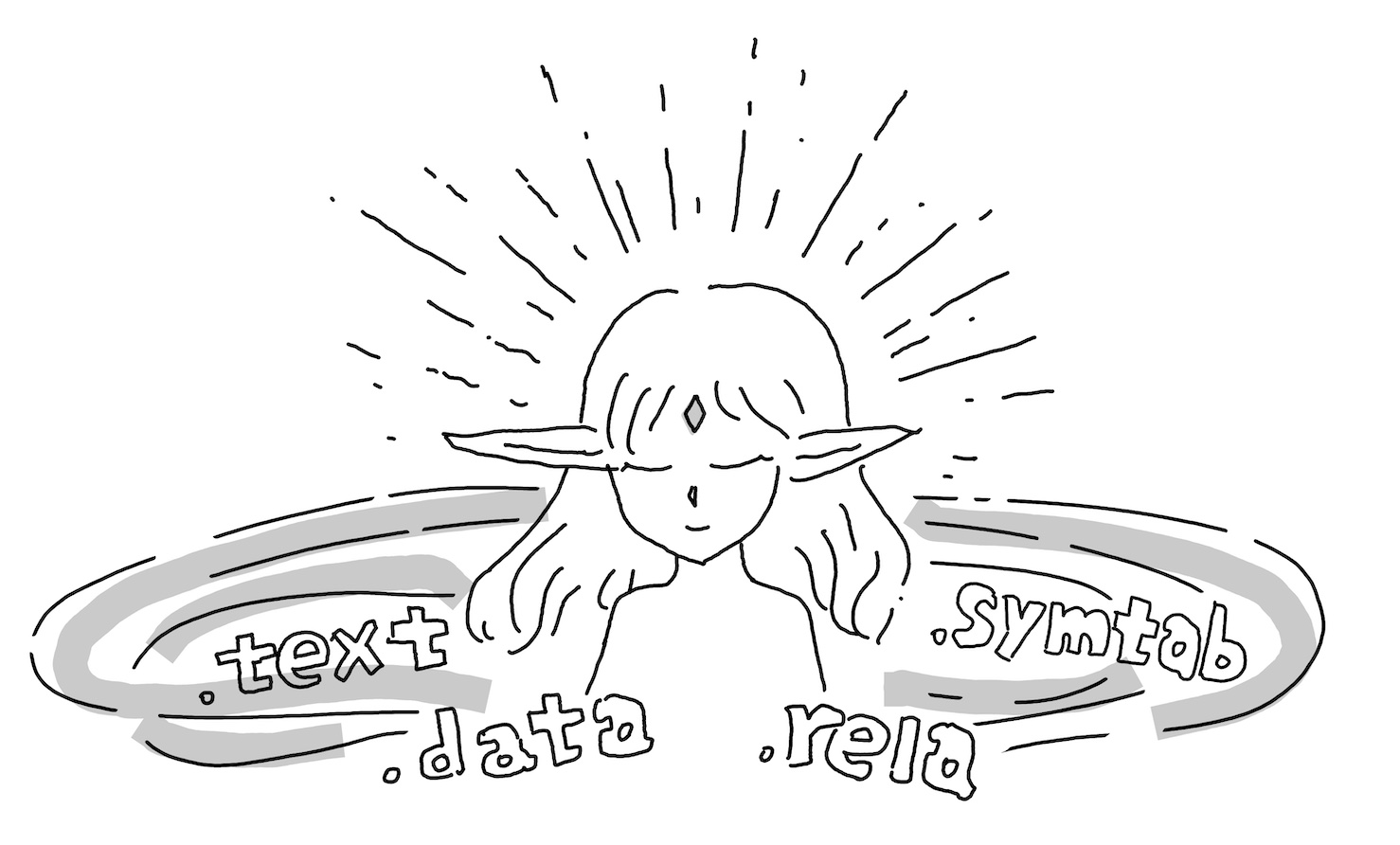

The Big Picture: What Does the Compiler Generate?

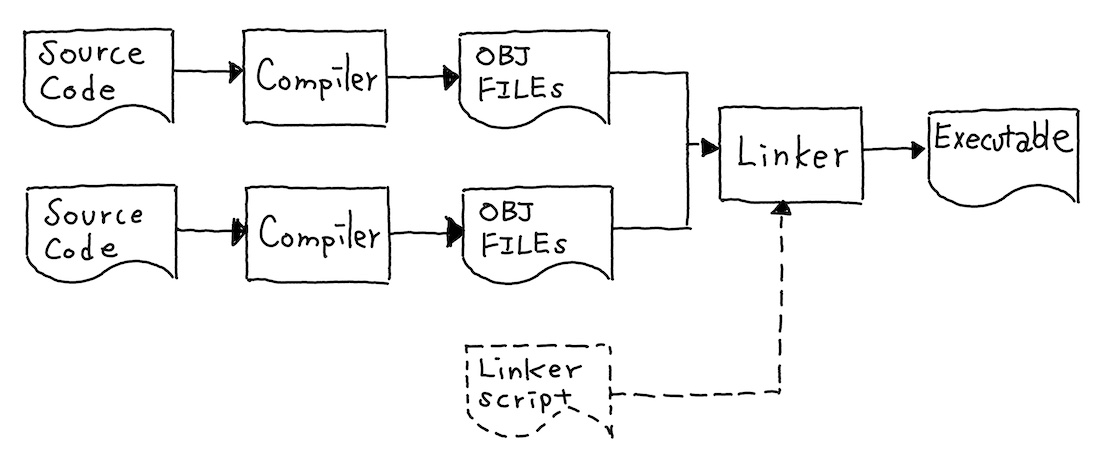

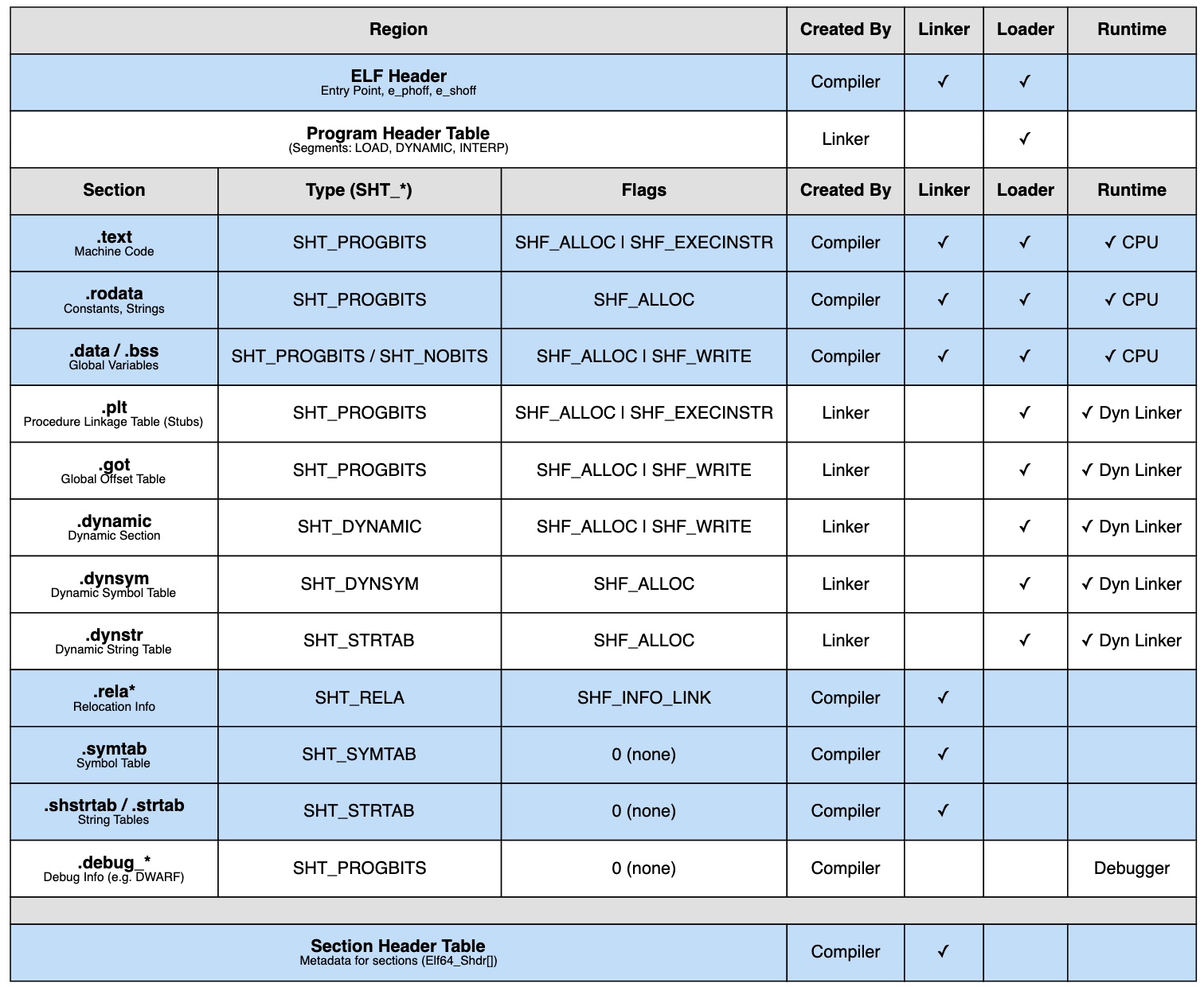

In Part I, we discussed how the linker resolves symbols and patches addresses. A key insight is that address resolution is not the compiler’s job, the compiler simply leaves placeholders for the linker to handle later. So what exactly does the compiler produce? Let’s look at the division of responsibilities:

The diagram shows which component creates each part of the ELF file. The blue regions are our responsibility as the compiler. We need to generate:

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

.text | Machine instructions (code) |

.rodata, .data, .bss | Constants and variables (data) |

.symtab | Symbol table: what functions and variables exist |

.rela.* | Relocation tables: what addresses need patching |

.strtab, .shstrtab | String tables: names for symbols and sections |

The linker will later add more sections (like .plt and .got for dynamic linking) and create the program header table.

The loader then uses these program headers to map everything into memory. But for now, let’s focus on what we’re building.

Setting Up: The Writer Framework

Let’s start with the skeleton of our object file writer. We’ll build it incrementally, adding features as we need them.

namespace obj_writer {

class Writer {

private:

std::vector<std::unique_ptr<Section>> sections;

std::unordered_map<std::string, size_t> sectionNameToIndex;

std::vector<elf::Elf64_Sym> symbols;

StringTable strTable;

public:

Writer();

size_t addSection(const std::string &name, ...);

Section *getSection(const std::string &name);

uint32_t addSymbol(const std::string &name, ...);

void addRelocation(Section *sec, ...);

bool writeToFile(const std::string &filename);

};

} // namespace obj_writerThe Writer class will be our main interface. It manages sections, symbols, relocation, and ultimately writes the ELF file.

But before we can write anything, we need to understand how binary data is stored.

First Challenge: Writing Binary Data Correctly

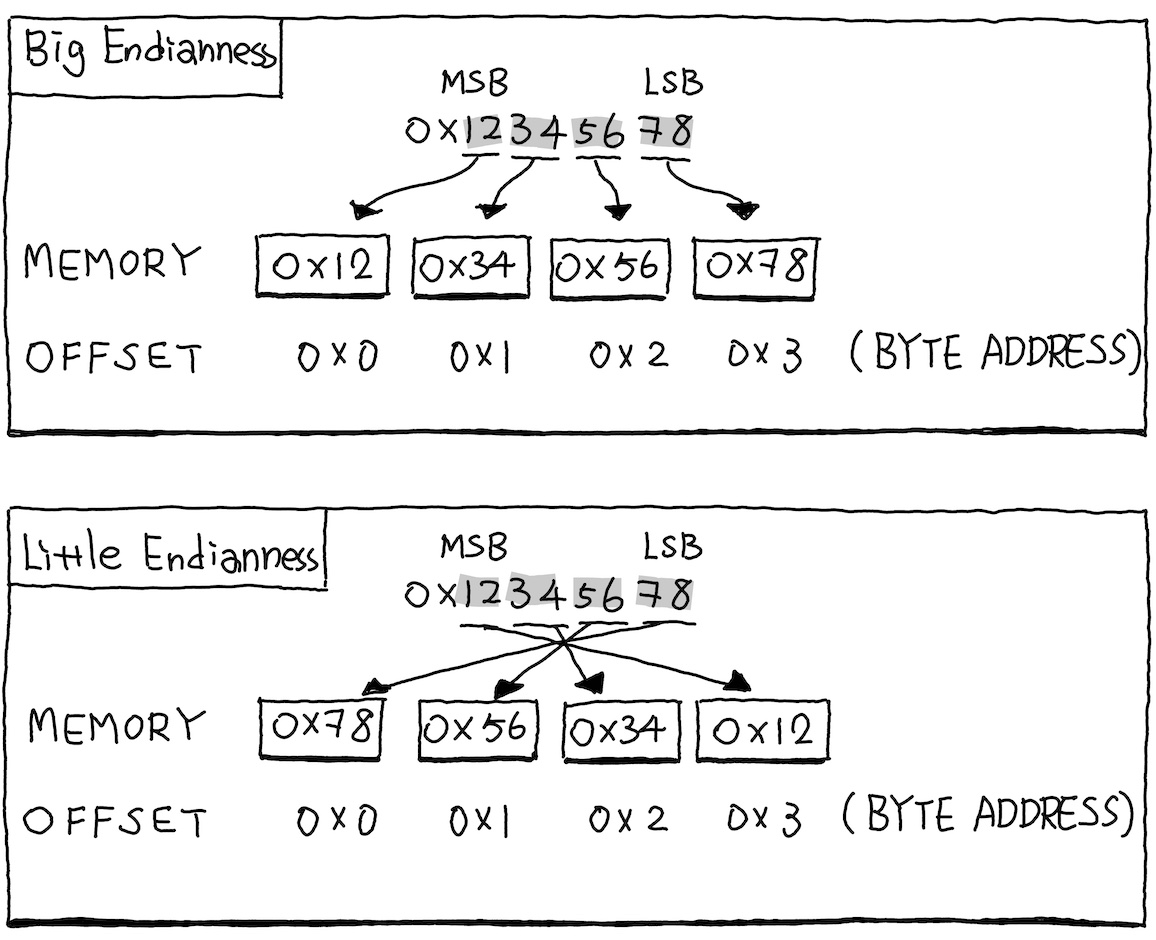

When writing machine code and data to a file, we immediately face a fundamental question: in what order do we write the bytes of a multi-byte value? Consider a 32-bit integer, it occupies 4 bytes in memory, but which byte comes first? There are two conventions:

- Little-endian: The least significant byte (LSB) comes first

- Big-endian: The most significant byte (MSB) comes first

The following figure illustrates how 0x12345678 is stored under each convention.

In little-endian, the bytes appear as 78, 56, 34, 12 where LSB at the lowest address.

In big-endian, they appear as 12, 34, 56, 78 where MSB at the lowest address.

ARM64 uses little-endian byte order, which means the least signficant byte is stored at the lowest address.

This might seem backwards at first, but it’s how the hardware expects data to be laid out.

When you inspect an ELF file with a hex editor, you’ll see bytes in little-endian order.

For example, the ARM64 ret instruction has the encoding 0xD65F03C0.

We can verify this with readelf or xxd:

$ readelf -x .text hello.o

Hex dump of section '.text':

0x00000000 fd7bbfa9 fd030091 00000090 00000091 .{..............

0x00000010 00000094 000080d2 fd7bc1a8 c0035fd6 .........{...._.$ xxd hello.o

...

00000050: ... fd7b c1a8 c003 5fd6 .........{...._.

...The bytes C0, 03, 5F, D6 appear in reverse order compared to the encoding 0xD65F03C0.

This is also recorded in the ELF header itself. The e_ident[5] field tells readers what byte order the file uses:

...

ehdr.e_ident[4] = 2; // ELFCLASS64 (64-bit)

ehdr.e_ident[5] = 1; // ELFDATA2LSB (little-endian)

ehdr.e_ident[6] = 1; // EV_CURRENT (ELF version 1)

...Since we’re running on a little-endian machine (x86-64 or ARM64) and generating little-endian output, we might wonder do we even need to handle byte swapping? In practice, NO, but we included the logic anyway for education purpose. Understanding endianness is fundamental to systems programming. Here’s our implementation:

namespace endian {

enum class Endianness { little, big };

// Detect host machine's endianness at startup

static const Endianness hostEndian = []() {

uint32_t test = 1;

// If the first byte is 1, we're little-endian

return *reinterpret_cast<uint8_t *>(&test) == 1

? Endianness::little : Endianness::big;

}();

} // namespace endianWe detect the endianness by creating an integer with value 1 and check which byte is non-zero.

In little-endian, the value 0x00000001 is stored as 01, 00, 00, 00, so the first byte is 1.

In big-endian, it’s stored as 00, 00, 00, 01, so the first byte is 0.

We provide a helper function to handle endianness conversion. The byteSwap function checks if byte swapping is needed. For single-byte types or when the target endianness matches the host endianness,

it simply returns the value unchanged. Otherwise, it reverses the byte order by treating the value as a byte array and using std::reverse.

The write function combines byte swapping with memory writing, it first converts the value to the target endianness using byteSwap, then copies the converted bytes to the destination using std::memcpy.

namespace endian {

template <typename T> T byteSwap(T value, Endianness targetEndian)

{

// No swap needed for single bytes or matching endianness

if (sizeof(T) <= 1 || targetEndian == hostEndian) {

return value;

}

// Reverse the bytes

T result = value;

uint8_t *bytes = reinterpret_cast<uint8_t *>(&result);

std::reverse(bytes, bytes + sizeof(T));

return result;

}

template <typename T> void write(uint8_t *dst, T value, Endianness endian)

{

T converted = byteSwap<T>(value, endian);

std::memcpy(dst, &converted, sizeof(T));

}

} // namespace endianThis is just one way to demonstrate the concept. If you look at LLVM’s implementation, you’ll find they also have

byteswap, but they use native endianness detection directly, so there’s no need for this kind of runtime check.

Building the Section Class

Now that we can write bytes correctly, let’s create a class to represent ELF sections. A section is simply a named chunk of binary data with some metadata.

class Section {

public:

std::string name; // Section name (e.g., ".text", ".rodata")

elf::Elf64_Word type; // Section type

elf::Elf64_Xword flags; // Section flags

elf::Elf64_Xword align; // Alignment requirement

endian::Endianness endian; // Byte order for this section

std::vector<uint8_t> data; // The actual bytes

uint64_t virtualSize = 0; // Size in memory (may differ from file size)

// ... methods ...

};The type field tells tools what kind of data the section contains. The most common types are:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

SHT_PROGBITS | Program data | Code or initialized data |

SHT_NOBITS | No bits | Uninitialized data (.bss), takes no space in file |

SHT_SYMTAB | Symbol table | Information about symbols |

SHT_STRTAB | String table | Null-terminated strings |

SHT_RELA | Relocations | Entries telling linker what to patch |

The flags field describes properties of the section:

| Flag | Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

SHF_ALLOC | Allocate | Section occupies memory at runtime |

SHF_WRITE | Writable | Section can be modified at runtime |

SHF_EXECINSTR | Executable | Section contains machine instructions |

For example, .text (code) has flags SHF_ALLOC | SHF_EXECINSTR, it’s loaded into memory and is executable.

.rodata (read-only data) has just SHF_ALLOC, loaded but not writable or executable.

.bss (uninitialized data) has SHF_ALLOC | SHF_WRITE, loaded, writable, but takes no space in the file.

Now let’s add methods to write data to a section:

// Emit a numeric value with correct endianness

template <typename T> void emit(T val)

{

size_t pos = data.size();

data.resize(pos + sizeof(T));

endian::write<T>(&data[pos], val, endian);

virtualSize += sizeof(T);

}

// Emit raw bytes (no endianness conversion)

void emitBytes(const void *src, uint64_t len)

{

size_t pos = data.size();

data.resize(pos + len);

std::memcpy(&data[pos], src, len);

virtualSize += len;

}The distinction between emit and emitBytes is important.

Use emit<T>() for numeric values that need endianness conversion, like instructions or normal data.

Use emitBytes() for raw data that’s already in the right format, like strings. After then, we

increase virtualSize to reflect the change of the offset in this section.

Creating Sections in the Writer

Now we can start to implement section management in the Writer class:

Writer::Writer()

{

// ELF requires a NULL section at index 0

addSection("", elf::SectionType::SHT_NULL, 0, 0, 0);

symbols.emplace_back();

}The writer initialization creates a section with SHT_NULL type at index 0.

ELF requires this NULL section as a sentinel value.

When a symbol’s st_shndx field is 0 (also called SHN_UNDEF), it indicates the symbol is undefined

(not defined in this object file and must be resolved by the linker).

We’ll see this when we create the printf symbol, which will have st_shndx = 0 because it’s defined

in the system’s C library, not in our object file, we need the linker to figure it out.

size_t Writer::addSection(const std::string &name, elf::Elf64_Word type,

elf::Elf64_Xword flags, elf::Elf64_Xword align,

elf::Elf64_Xword entsize)

{

size_t idx = sections.size();

auto [it, inserted] = sectionNameToIndex.insert({name, idx});

if (inserted) {

sections.emplace_back(std::make_unique<Section>(

name, type, flags, align, entsize, endian));

return idx;

}

return it->second;

}The addSection function creates a new section and returns its index. When a section with the given name

doesn’t exist yet, it creates the section and records the mapping from section name to its index in sectionNameToIndex.

If the section already exists, it simply returns the existing index, avoiding duplicates.

In essence, this function creates an empty section container that will later be populated with data via emit calls,

or referenced by symbols through their st_shndx field, which stores the section index where the symbol is defined.

Our First Section for The String “hello world”

Let’s create our first real section: .rodata.str1.1 to hold our “hello world” string.

obj_writer::Writer writer;

// Create .rodata.str1.1 for string literals

size_t rodataIdx = writer.addSection(

".rodata.str1.1",

SHT_PROGBITS,

SHF_ALLOC | SHF_MERGE | SHF_STRINGS,

1, // alignment: 1 byte (strings don't need alignment)

1 // entry size: 1 (for mergeable string sections)

);

Section *rodata = writer.getSection(".rodata.str1.1");The flags SHF_MERGE | SHF_STRINGS tell the linker that this section contains null-terminated strings

that can be merged with identical strings from other object files. This is a space optimization, if

two source files both use the string “hello”, the linker only needs to keep one copy.

std::string helloStr = "hello world\n";

uint64_t helloStrOffset = writer.emitData(rodata, helloStr);The emitData helper writes the string into the rodata section. It handles strings specially,

writes the bytes and appends a null terminator.

template <typename T> uint64_t emitData(Section *sec, T &&val)

{

using RawType = std::remove_cv_t<std::remove_reference_t<T>>;

if constexpr (std::is_same_v<RawType, std::string> ||

std::is_same_v<RawType, std::string_view>) {

uint64_t offset = sec->virtSize();

sec->emitBytes(val.data(), val.size());

sec->emit<uint8_t>(0); // Null terminator

return offset;

}

// ... handle other types ...

}After this, our .rodata.str1.1 section contains 13 bytes: hello world\n\0.

The returned offset tells us where in the section our string starts, we’ll need this for relocations.

From the compiler’s perspective, the address of this string is unknown at compile time.

The linker will decide the final address layout when combining multiple object files, so we can only

know the relative position (offset) within the section. When we later reference this string in our code,

we’ll use relocations to tell the linker: “patch this instruction with the address of the string at offset X.”

The Code Section: Writing Machine Instructions

The .text section contains our machine code, the actual executable instructions that the CPU will run.

It’s marked with SHF_ALLOC | SHF_EXECINSTR flags, meaning it will be loaded into memory and is executable.

The alignment is 4 because ARM64 instructions must be 4-byte aligned.

size_t textIdx = writer.addSection(

".text",

SHT_PROGBITS,

SHF_ALLOC | SHF_EXECINSTR,

4 // alignment: 4 bytes (ARM64 instructions are 4 bytes)

);

Section *text = writer.getSection(".text");Encoding ARM64 Instructions

Before we can emit instructions, we need to understand how ARM64 instructions are encoded. Unlike 32-bit ARM architectures that support both 32-bit and 16-bit THUMB instructions, ARM64 uses a fixed-length instruction format which every instruction is exactly 32 bits (4 bytes). The bits are divided into fields that specify the operation, registers, and immediate values. There are two official resources are highly recommended: the ARM64 Instruction Set Architecture Guide and the ARM64 Instruction Encoding Reference.

Let’s look at some helper functions:

namespace arm64 {

// Return from subroutine

uint32_t ret() { return 0xD65F03C0; }

// bl <offset> : Branch with link (function call)

uint32_t bl() { return 0x94000000; }

// adrp Xd, <label> : Load page address

uint32_t adrp(uint8_t rd) {

return (1 << 31) | (0b10000 << 24) | rd;

}

// add Xd, Xn, #imm : Add immediate

uint32_t add_imm(uint8_t rd, uint8_t rn) {

return (1 << 31) | (0b0010001 << 24) | (rn << 5) | rd;

}

} // namespace arm64Notice that bl() returns 0x94000000, the offset field is zero. Similarly, adrp() and add_imm() have

their immediate fields set to zero. These are placeholders that the linker will fill in based on our relocation entries.

However, this approach has limitations: the hard-coded instruction encodings don’t properly handle cases where immediate fields aren’t used for relocations. In a later post, we’ll build a complete operation table where operands strictly adhere to the ISA specification.

The Function Prologue

Every function needs a prologue to set up its stack frame. On ARM64, this typically saves the frame pointer (x29)

and link register (x30), then updates the frame pointer:

// stp x29, x30, [sp, #-16]! ; Save fp and lr, decrement sp by 16

writer.emitInstruction(text, arm64::stp_pre_64(-2, 30, 31, 29));

// mov x29, sp ; Set frame pointer to current sp

writer.emitInstruction(text, arm64::add_imm(29, 31));The stp (store pair) instruction saves two registers at once. The -2 means offset is -16 bytes.

The immediate is scaled by 8 for 64-bit registers. The ! in assembly notation indicates pre-indexing,

the stack pointer is decremented before the store.

You might notice that we use add_imm, but objdump displays it as mov. When we encode add_imm(29, 31)

with immediate 0, it produces the machine code for add x29, x31, #0 (where register 31 is sp).

When you disassemble the object file with objdump, it recognizes this common pattern and displays it

as the more readable mov x29, sp pseudo-instruction. The actual machine code is still add x29, sp, #0.

Inside emitInstruction: Three Critical Steps

The emitInstruction helper does more than just write bytes, it ensures correctness for ARM64 code generation.

Let’s examine each step:

void Writer::emitInstruction(Section *sec, uint32_t instr)

{

// Step 1: Ensure 4-byte alignment

emitAlignment(sec, 4);

// Step 2: Mark this region as code (for ARM mapping symbols)

switchContent(sec, Section::ContentState::Code);

// Step 3: Write the instruction

sec->emit<uint32_t>(instr);

}Step 1: Alignment (emitAlignment)

ARM64 requires instructions to be aligned to 4-byte boundaries. If you try to execute an instruction at

an unaligned address (e.g., 0x1001 instead of 0x1000), the CPU will raise an alignment fault and crash.

Why might we be unaligned? Consider a section that mixes code and data. If we emit a 5-byte string followed

by an instruction, we’d be at offset 5, not a multiple of 4. The emitAlignment function adds padding bytes

to reach the next aligned offset:

void Writer::emitAlignment(Section *sec, uint64_t align)

{

uint64_t currentOffset = sec->virtSize();

uint64_t padding = (align - (currentOffset % align)) % align;

if (sec->lastState == Section::ContentState::Code) {

// In code regions, pad with NOP instructions

sec->emitPadding(padding, 0xD503201F); // ARM64 NOP

} else {

// In data regions, pad with zeros

sec->emitPadding(padding, 0x00);

}

}Notice that we use different padding values depending on context:

- In code regions: We pad with

NOPinstructions (0xD503201F). This is important because if the CPU somehow executes the padding,NOPdoes nothing harmful. - In data regions: We just pad with zeros.

Step 2: Mapping Symbols (switchContent)

ARM64 ELF files require special “mapping symbols” to mark transitions between code and data. This is specified in the ARM ELF ABI’s Mapping Symbols:

“All mapping symbols have type

STT_NOTYPEand bindingSTB_LOCAL. The st_size field is unused and must be zero.”

The mapping symbols are:

$x: marks the beginning of a sequence of ARM64 instructions$d: marks the beginning of a sequence of data

A section might contain both code and inline data, like literal pools or jump tables. Without mapping symbols, disassemblers wouldn’t know which bytes are instructions and which are data. They might try to disassemble data as code, producing garbage output.

void Writer::switchContent(Section *sec, Section::ContentState reqState)

{

// Only emit a mapping symbol when the state actually changes

if (sec->lastState != reqState) {

std::string symName =

(reqState == Section::ContentState::Code) ? "$x" : "$d";

addSymbol(symName,

STB_LOCAL, // symbol binding

STT_NOTYPE, // symbol type

getSectionIndex(sec), // the index of the section

sec->virtSize(),

0 /* size: mapping symbols must have st_size = 0 */);

sec->lastState = reqState;

}

}The function tracks the current state (code vs. data) and only emits a new mapping symbol when switching.

For our “Hello World” example, when we first emit data to .rodata.str1.1, we emit a $d symbol at offset 0.

And similarly, the first emit code to .text, we emit a $x symbol at offset 0.

You can see these in the symbol table output:

$ readelf -s hello.o

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

2: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 2 $d

3: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 1 $xThe addSymbol function creates a new entry in the symbol table, which we just covered in the next section,

the The Symbol Table.

Step 3: Emit the Instruction (sec->emit<uint32_t>)

Finally, we write the 4-byte instruction to the section’s buffer using emit<T>(),

which we already covered in the Building the Section Class section.

The Symbol Table: Telling the Linker What Exists

So far we’ve written code and data, but the linker doesn’t know anything about them yet. We need to tell it about the symbols (names) in our program. This is what the symbol table is for.

Each symbol has several properties:

struct Elf64_Sym {

Elf64_Word st_name; // Offset into string table

unsigned char st_info; // Type and binding (packed into one byte)

unsigned char st_other; // Must be zero; reserved

Elf64_Half st_shndx; // Section index where symbol is defined

Elf64_Addr st_value; // Symbol value (usually offset within section)

Elf64_Xword st_size; // Size of the symbol (e.g., function size)

};The st_info field packs two pieces of information:

- Binding (high 4 bits): Is it local, global, or weak

- Type (low 4 bits): Is it a function, variable, section, etc.

| Binding | Value | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

STB_LOCAL | 0 | Only visible within this file |

STB_GLOBAL | 1 | Visible to other files |

STB_WEAK | 2 | Like global, but can be overridden |

| Type | Value | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

STT_NOTYPE | 0 | Not specified |

STT_OBJECT | 1 | Data object (variable) |

STT_FUNC | 2 | Function |

STT_SECTION | 3 | Section (used for relocations) |

We use addSymbol helper function to create it.

It will construct a symbol, put it into to the symbols and return its index.

uint32_t Writer::addSymbol(const std::string &name, uint8_t bind, uint8_t type,

uint16_t shndx, uint64_t value, uint64_t size)

{

uint32_t index = symbols.size();

symbols.emplace_back();

elf::Elf64_Sym &sym = symbols.back();

// st_name is the offset of the string in the string table

sym.st_name = name.empty() ? 0 : strTable.add(name);

sym.setBindingAndType(bind, type);

sym.st_other = 0;

sym.st_shndx = shndx;

sym.st_value = value;

sym.st_size = size;

return index;

}For our “Hello World” program, we need three symbols,

// 1. Section symbol for .rodata.str1.1

// Used by relocations to reference the string section

uint32_t symRodata = writer.addSymbol(

"", // No name (section symbols are anonymous)

STB_LOCAL, STT_SECTION, // Local, section type

rodataIdx, // Defined in .rodata.str1.1

0 // Value: 0 (start of section)

);

// 2. The main function

// This is what the linker looks for as the program entry point

uint32_t symMain = writer.addSymbol(

"main", // Name: "main"

STB_GLOBAL, STT_FUNC, // Global function

textIdx, // Defined in .text

0 // Value: 0 (offset in .text)

);

// 3. The printf function (external)

// We call this but don't define it, the linker will help us to find it

uint32_t symPrintf = writer.addSymbol(

"printf", // Name: "printf"

STB_GLOBAL, STT_NOTYPE, // Global, no specific type

SHN_UNDEF, // Section: UNDEFINED

0 // Value: 0 (not defined here)

);The critical difference is symPrintf’s section index: SHN_UNDEF (0). This tells the linker that

it need a symbol called printf, but it’s not defined in this file.

The linker will search through other object files and libraries until it finds printf

(typically in libc). If it can’t find it, you get the dreaded “undefined reference” error.

String Tables: Where Names Are Stored

You might have noticed that Elf64_Sym::st_name is an integer, not a string. ELF doesn’t store

symbol names directly in the symbol table. Instead, it stores offsets into a separate string table.

Why? Because many symbols share common prefixes or are duplicated across sections. A string table allows efficient storage and sharing of strings.

Our StringTable class handles this:

uint32_t StringTable::add(std::string s)

{

// Empty string always at offset 0

if (s.empty()) {

return 0;

}

// Check if we've seen this string before

if (auto it = cache.find(s); it != cache.end()) {

return it->second; // Return cached offset

}

// Append the new string

size_t offset = data.size();

data.resize(offset + s.size() + 1);

std::memcpy(&data[offset], s.data(), s.size());

data[offset + s.size()] = 0; // Null terminator

cache.emplace(std::move(s), offset);

return static_cast<uint32_t>(offset);

}The string table always starts with a null byte (empty string at offset 0). When we add a string, we append it followed by a null terminator, and return the offset where it starts.

There are actually two string tables in an ELF file:

.strtab: Holds symbol names.shstrtab: Holds section names

Our Writer just only maintains .strtab internally and

creates .shstrtab when writing the ELF file automatically.

Relocations: The Placeholders for the Linker

Now we come to the heart of how compilation works: relocations. Think of relocations as placeholders, that promises from the compiler to the linker that certain addresses need to be filled in later.

When we emit the bl printf instruction, we don’t know where printf will end up in memory.

The linker decides that later, after combining all object files. So we emit the instruction with

a placeholder and add a relocation entry that says: “Hey linker, please patch this location with the address of printf.”

Each relocation entry contains:

struct Elf64_Rela {

Elf64_Addr r_offset; // Where to patch (offset within section)

Elf64_Xword r_info; // Symbol index + relocation type

Elf64_Sxword r_addend; // Value to add to the symbol's address

};The r_info field packs two values:

- Upper 32 bits: Index into the symbol table

- Lower 32 bits: Relocation type, how to calculate and encode the value

Different relocation types tell the linker how to compute the patch value. For a complete reference of AArch64 relocation types, see the ARM ELF ABI’s Relocation Types. We use the following types in our example:

| Type | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

R_AARCH64_CALL26 | 283 | 26-bit PC-relative offset for bl instruction |

R_AARCH64_ADR_PREL_PG_HI21 | 275 | High 21 bits of page address for adrp |

R_AARCH64_ADD_ABS_LO12_NC | 277 | Low 12 bits of address for add |

Loading the String Address

On ARM64, we can’t load a 64-bit address in a single instruction. Instead, we use a two-instruction sequence:

adrp x0, <label>: Load the address of the 4KB page containing the labeladd x0, x0, <offset>: Add the offset within the page

This is why we need two relocations for our string:

// adrp x0, hello_str

uint64_t adrpOffset = text->virtSize();

writer.emitInstruction(text, arm64::adrp(0));

writer.addRelocation(text, adrpOffset, symRodata,

R_AARCH64_ADR_PREL_PG_HI21, helloStrOffset);

// add x0, x0, :lo12:hello_str

uint64_t addOffset = text->virtSize();

writer.emitInstruction(text, arm64::add_imm(0, 0));

writer.addRelocation(text, addOffset, symRodata,

R_AARCH64_ADD_ABS_LO12_NC, helloStrOffset);The addend parameter (helloStrOffset) is added to the symbol’s address. Since our string is at

offset 0 in the .rodata.str1.1 section, the addend is 0. But if we had multiple strings, each would

have a different offset.

Calling printf

The bl (branch with link) instruction takes a 26-bit signed offset, allowing jumps of ±128 MB.

The linker calculates this offset from the instruction’s address to printf’s address:

// bl printf

uint64_t blOffset = text->virtSize();

writer.emitInstruction(text, arm64::bl());

writer.addRelocation(text, blOffset, symPrintf,

R_AARCH64_CALL26, 0);The R_AARCH64_CALL26 relocation type tells the linker to calculate the PC-relative offset to the symbol,

divide by 4 (since instructions are 4-byte aligned), and encode it in bits [25:0] of this instruction.

And more importantly, don’t forget the symbol symPrintf and blOffset (The start address of the instruction),

otherwise the linker won’t know which symbol this relocation refers to and where it needs to patch.

The Function Epilogue and Return

After calling printf, we set the return value to 0 and restore the saved registers:

// mov x0, #0 ; Return 0

writer.emitInstruction(text, 0xD2800000);

// ldp x29, x30, [sp], #16 ; Restore fp and lr, increment sp

writer.emitInstruction(text, arm64::ldp_post_64(2, 30, 31, 29));

// ret ; Return to caller

writer.emitInstruction(text, arm64::ret());The ldp (load pair) instruction is the inverse of stp: it restores the two registers and

increments the stack pointer. The ret instruction jumps to the address in x30 (the link register).

Finally, we update the main symbol’s size so debuggers know where the function ends:

uint64_t funcEnd = text->virtSize();

writer.setSymbolSize(symMain, funcEnd - funcStart);Writing the ELF File

Now we have all the pieces: sections with code and data, symbols, and relocations.

Let’s see how Writer::write() assembles them into a valid ELF file.

Step 1: Sort Symbols

ELF requires local symbols to come before global symbols in the symbol table. We need to sort them:

// Sort symbols: locals first, then globals

std::vector<size_t> indices(symbols.size());

std::iota(indices.begin(), indices.end(), 0);

std::stable_sort(indices.begin(), indices.end(), [&](size_t a, size_t b) {

// binding type: LOCAL < GLOBAL

return symbols[a].getBinding() < symbols[b].getBinding();

});

// Reorder and build old-to-new index mapping

std::vector<size_t> oldToNew(symbols.size());

std::vector<Elf64_Sym> sortedSymbols;

for (size_t i = 0; i < indices.size(); ++i) {

oldToNew[indices[i]] = i;

sortedSymbols.push_back(std::move(symbols[indices[i]]));

}

symbols = std::move(sortedSymbols);We also need to update all relocation entries to use the new symbol indices:

for (auto &sec : sections) {

for (auto &rela : sec->relocations) {

uint32_t oldSym = rela.getSymbol();

uint32_t type = rela.getType();

rela.setSymbolAndType(oldToNew[oldSym], type);

}

}Step 2: Create Meta Sections

The writer automatically creates several meta sections that ELF requires:

// Section name string table

size_t shstrtabIdx = addSection(".shstrtab", SHT_STRTAB, 0, 1);

// Symbol string table

size_t strtabIdx = addSection(".strtab", SHT_STRTAB, 0, 1);

// Symbol table

size_t symtabIdx = addSection(".symtab", SHT_SYMTAB, 0, 8, sizeof(Elf64_Sym));

// Relocation sections for each section that has relocations

for (size_t i = 0; i < sections.size(); ++i) {

if (!sections[i]->relocations.empty()) {

std::string relaName = ".rela" + sections[i]->name;

addSection(relaName, SHT_RELA, SHF_INFO_LINK, 8, sizeof(Elf64_Rela));

}

}For our “Hello World”, this creates:

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

.shstrtab | Section names |

.strtab | Symbol names |

.symtab | The symbol table |

.rela.text | Relocations for .text |

Note that .shstrtab (section name string table) is handled differently from .strtab (symbol name string table).

While .strtab is built incrementally as we add symbols, .shstrtab is populated automatically at write time

by iterating through all sections and collecting their names:

// Build Section Name String Table

StringTable shStrTab;

std::vector<uint32_t> secNameOffsets(sections.size());

for (size_t i = 0; i < sections.size(); ++i) {

secNameOffsets[i] = shStrTab.add(sections[i]->name);

}

sections[shstrtabIdx]->data.assign(shStrTab.getBuffer().begin(),

shStrTab.getBuffer().end());

sections[shstrtabIdx]->virtualSize = shStrTab.getBuffer().size();This approach makes sense because section names are only known after all sections have been created,

including the meta sections themselves. The secNameOffsets array stores each section’s name offset,

which will be used when writing section headers.

Step 3: Calculate Offsets

Each section needs a file offset. We calculate these while respecting alignment requirements, and the actual data will be written to these offsets in the later step.

std::vector<elf::Elf64_Shdr> shdrs(sections.size());

uint64_t currentOffset = sizeof(Elf64_Ehdr); // Start after ELF header

for (size_t i = 0; i < sections.size(); ++i) {

auto &sec = sections[i];

// Align current offset

if (sec->align > 1) {

uint64_t padding =

(sec->align - (currentOffset % sec->align)) % sec->align;

currentOffset += padding;

}

shdrs[i].sh_offset = currentOffset;

shdrs[i].sh_size = sec->virtSize();

currentOffset += sec->fileSize(); // NOBITS sections have fileSize() = 0

}Step 4: Write the ELF Header

The ELF header is the first 64 bytes of the file and serves as the “table of contents” for the entire ELF file. It tells tools how to interpret the rest of the file.

Elf64_Ehdr ehdr = {};

// Magic number: 0x7f 'E' 'L' 'F'

ehdr.e_ident[0] = 0x7f;

ehdr.e_ident[1] = 'E';

ehdr.e_ident[2] = 'L';

ehdr.e_ident[3] = 'F';

ehdr.e_ident[4] = 2; // ELFCLASS64: 64-bit

ehdr.e_ident[5] = 1; // ELFDATA2LSB: Little-endian

ehdr.e_ident[6] = 1; // EV_CURRENT: ELF version 1

ehdr.e_type = ET_REL; // Relocatable object file

ehdr.e_machine = 183; // EM_AARCH64

ehdr.e_version = 1;

ehdr.e_shoff = currentOffset; // Section headers at end of file

ehdr.e_ehsize = sizeof(Elf64_Ehdr);

ehdr.e_shentsize = sizeof(Elf64_Shdr);

ehdr.e_shnum = sections.size();

ehdr.e_shstrndx = shstrtabIdx; // Which section has section names

os.write(reinterpret_cast<char *>(&ehdr), sizeof(ehdr));Let’s break down each field:

The e_ident array (16 bytes) — This is the ELF identification:

e_ident[0..3]: The magic number0x7f,E,L,F. Any tool can check these 4 bytes to quickly determine if a file is ELF format.e_ident[4]: File class.2means 64-bit (ELFCLASS64). Use1for 32-bit.e_ident[5]: Data encoding.1means little-endian (ELFDATA2LSB). Use2for big-endian.e_ident[6]: ELF version. Always1for the current specification.e_ident[7..15]: Padding, typically zeros.

File type and machine:

e_type: We useET_RELfor relocatable object files. We cannot useET_EXEC(executable) because our object file still contains unresolved symbols (likeprintf) and relocations that need to be patched. Only after the linker resolves all symbols and assigns final virtual addresses can the file become an executable. Other values includeET_DYNfor shared libraries (.sofiles).e_machine:183isEM_AARCH64for ARM64.

Section header information:

e_shoff: File offset where the section header table begins. We place it at the end of the file.e_ehsize: Size of this ELF header (64 bytes for ELF64).e_shentsize: Size of each section header entry (64 bytes forElf64_Shdr).e_shnum: Number of section headers.e_shstrndx: Index of the section that contains section names (.shstrtab).

Fields we leave as zero:

e_entry: Entry point address. For object files, this is 0 because they’re not directly executable.e_phoff,e_phentsize,e_phnum: Program header information. This is not our reponsibility to create them, so these are all 0.e_flags: Processor specific flags. For basic AArch64, this is 0.

Step 5: Write Section Data and Headers

Finally, we write each section’s data, adding padding as needed, then the section header table at the end:

// Write section contents

for (size_t i = 1; i < sections.size(); ++i) {

// NOBITS has no file data for .bss

if (sections[i]->type == SHT_NOBITS) continue;

// Add padding to reach required offset

uint64_t fpos = os.tellp();

if (shdrs[i].sh_offset > fpos) {

std::vector<char> pad(shdrs[i].sh_offset - fpos, 0);

os.write(pad.data(), pad.size());

}

os.write(reinterpret_cast<const char *>(sections[i]->data.data()),

sections[i]->data.size());

}

// Write section header table

os.write(reinterpret_cast<char *>(shdrs.data()),

sizeof(Elf64_Shdr) * shdrs.size());Testing Our Generator

Let’s compile and run our generator:

$ make

g++ main_hello.cpp obj_writer.cpp --std=c++20 -o gen

$ ./gen

Successfully generated hello.o

Run `gcc -o hello hello.o` to link the object file into an executable.We can inspect the generated file with standard tools:

$ file hello.o

hello.o: ELF 64-bit LSB relocatable, ARM aarch64, version 1 (SYSV), not stripped$ readelf -h hello.o

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: REL (Relocatable file)

Machine: AArch64

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x0

Start of program headers: 0 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 408 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x0

Size of this header: 64 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 0 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 0

Size of section headers: 64 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 7

Section header string table index: 3Let’s look at the symbol table:

$ readelf -s hello.o

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 6 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 2 .rodata.str1.1

2: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 2 $d

3: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT 1 $x

4: 0000000000000000 32 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 main

5: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE GLOBAL DEFAULT UND printfNotice printf has Ndx: UND, it’s undefined, as expected. The linker will resolve it.

And the relocations:

$ readelf -r hello.o

Relocation section '.rela.text' at offset 0x150 contains 3 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

000000000008 000100000113 R_AARCH64_ADR_PRE 0000000000000000 .rodata.str1.1 + 0

00000000000c 000100000115 R_AARCH64_ADD_ABS 0000000000000000 .rodata.str1.1 + 0

000000000010 00050000011b R_AARCH64_CALL26 0000000000000000 printf + 0Three relocations, exactly as we planned. Two for loading the string address (adrp + add).

One for calling printf (bl).

Now let’s link and run:

$ gcc -o hello hello.o

$ ./hello

hello worldGood! We’ve generated a valid ELF object file entirely from scratch!

Key Takeaways

If there’s one thing I hope you take away from this post, it’s that ELF isn’t some mysterious black box. it’s just a well-structured file format. Once you understand its components (headers, sections, symbols, relocations), the whole picture becomes clear.

The compiler’s role is surprisingly focused: we generate machine code, organize data and instructions into sections, create symbol tables, and leave relocation entries as placeholders for addresses we don’t know yet. We’re not trying to solve everything; we’re just preparing the pieces for the linker to assemble.

Speaking of relocations, think of them as leaving notes for the linker: “Hey, when you figure out where printf lives, patch this instruction with the right offset.”

This division of responsibility, compiler generates, linker resolves, is what makes the whole system work.

Symbols are the glue that holds everything together. They’re how we tell the linker “here’s a function called main” or “we need something called printf but don’t have it.”

Without symbols, the linker would have no idea what to connect to what.

Finally, those mapping symbols ($x and $d) might seem like an odd detail, but they’re what let tools like objdump correctly disassemble your code.

Without them, a disassembler might try to interpret data as instructions, producing garbage output.

What’s Next

I’ll be honest, this post was heavy on format details, alignment calculations, and offset management. These aren’t the most exciting topics, but they’re the foundation that makes everything else possible. If you have ideas on how to make this material more engaging 😅, or if you run into any issues, please feel free to open an issue on the repository.

In the next post, we’ll build a complete operation table for ARM64 instructions. This will replace the hard-coded instruction encodings we used here.

Further Reading

- OS Dev ELF - A well known website for os dev, they also covered the ELF format

- ELF Doc - A complete ELF doc

- ELF Cheetsheet - A cheetsheet created by x0nu11byt3

- AArch64 ELF’s Doc - Since we are using AARCh64, we must need the AARCh64’s ELF specification